By ERIC O'KEEFE

Katie the dog died in October, while I was away. There is a depression in the carpet at my parents' house where my father sits each night to watch television. He pets the dogs there. I have rarely seen him sit on the couch in the normal way, save the occasional Emergency Family Meeting or when company comes over who we are trying to impress. He prefers the carpeted floor, where he leans back, big dad bellyingly onto the couch with his legs outstretched and arms crossed.

The first time I saw my father cry was when we put down the original family dog, Daisy. Both of my grandparents on his side are dead. As an adult my grandparents' memory does not serve save as a warning to the dangers of our Irish blood, which left them distant and disengaged, but all I truly remember are veined hands reaching into a purse for Daisy's treat and games of chess I was too young to understand.

Daisy had long blonde hair that made her seem wise, and she was wise. She was a medium-sized dog, around 55 pounds, but for my size back then she was enormous. While I sucked my thumb I would use her curled torso as a back rest and sleep on the floor, and she had the patience to let me nap wrapped in the safety of her legs, even though she had more important dog affairs she could have attended to. My dad chose to stay in the back room at the vet's office where she was euthanized, and that is when I first caught him crying: while being escorted away after saying goodbye to Daisy. I still remember the door closing on the two of them, his arms enveloping her now small, sedated body, whispering “good girl, good girl” with a heavy lip to ease her passing.

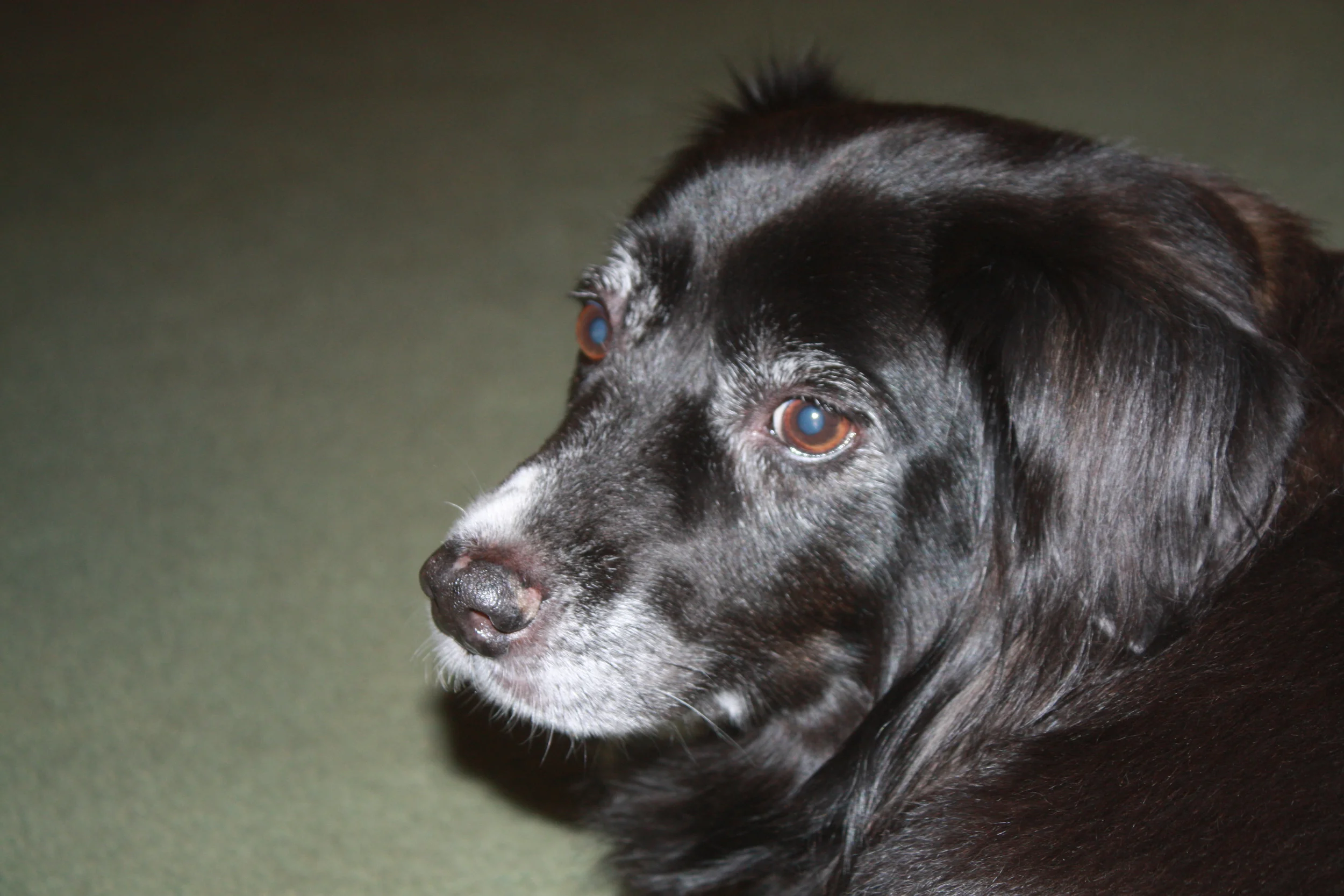

I wanted the other puppy at the shelter after Daisy died. The other puppy was blonde and reminded me of Daisy; Katie was black and small. My parents decided on Katie because her docile nature complimented our young and growing family. I came to love Katie but we had a complicated relationship, mostly on her end. The first week we had her I stepped on her hind leg and she yelped and cried and I ran away to the house and immediately wept, not helping her. I don’t think she ever really got over it. As she aged Katie’s hips went bad and she walked with a limp. I always looked to see which leg she favored.

Katie had a problem with boundaries, or rather, I had a problem with Katie’s boundaries. In the right mood she would consent to a belly rub, but as a rule that which was vulnerable was off limits. I was always pushing those limits. She was not afraid to bite, but always as more of a ‘fuck off’ than an aggressive act. We would occasionally get into standoffs, me with my forearm pinched between her teeth and she with a growl, our eyes locked, daring each other to make the next move. She was a good dog though: she would always ease off and be the bigger man.

She also did not appreciate my attempts to change her worldview. As I exited puberty, her size relative to mine had changed, as had our relationship. Being a short dog, Katie had a limited perception of her surroundings that I tried, with my new size and strength, to broaden. With the purest of intentions I would illuminate her to the world of the humans by lifting her to our level in order to see what we saw - the kitchen counter, what was on top of the fridge, what was inside the cabinets. She of course growled when I did this, but only as I picked her up or just before I set her down. She would always quiet down when I showed her new things.

The third dog came suddenly and without consultation. His arrival coincided with thestretches of free time my father now had in the wake of the 2008 recession. His name was Charlie, and he was a tiny dog. Charlie was white and afraid of everything, as anything burrito-sized should be. As a six-foot, three-inch tall adult my size intimidated Charlie, and although he was playful, he could never trust my rough housing without a healthy dose of fear. He was a fancy dog, needing more care than the other two dogs combined. My father loved the extra maintenance though, content with the love inherent in utter dependence.

I came home one holiday season and Katie was fat. My father was at fault, apparently. He kept her treats in the pantry his wine was stored in and fed her whenever he refilled his glass. It became a sort of ritual when I came home, to offer my opinion of at first Katie’s and then Charlie’s weight, my assessment forging alliances in the much bigger war between my parents.

Towards the end of her life, Katie had my father trained. Being a short dog, she fit perfectly height-wise with my father on the floor. She would nuzzle right up to him and rest her head on his chest, her tail slowly wagging in anticipation of the next trip to the pantry. Charlie would flank him on the other side, not fully understanding but happy to be included. When I watched movies or the news with my father I would look at him there, draped on both sides with dogs waiting patiently for his sign. That image is what came to me as I heard of Katie’s death—my father and the wine and the carpet with one less dog bathed in the blue of the screen, with my mother in some other room mourning in her own silent way, the rest of the house dark in night.

Eric O'Keefe is a seasonal carpenter who lives in Alaska. Sometimes. He picks a guitar and hails from Maryland. He enjoys the silence of beautiful spaces. He loves strong coffee and having too much free time.