BY DEVON MIDORI HALE

Not many people know that I own a truck.

A pickup is an unspoken communal vehicle. People with trucks are accustomed to getting certain calls from all of their friends: friends asking for help moving and hauling in exchange for lunch, unlimited beers, or stacks of social credit. My truck is like a best-kept secret that I don’t often share with others since it might break down at the worst moment. It’s not exactly the safest to drive around in, and I try to keep that liability to myself.

My truck is a sky blue 1986 Chevy S10. My truck and I are the exact same age. As a young Asian woman, this old beater works like a charm, as if it somehow wards off the usual stereotypes: bad driver, ultra-feminine, exotic, obedient, quiet, and so on.

My ninety-four year old grandfather handed down his truck to me when his kids pointed out that it was just sitting in his driveway unused. The truck’s appraisal is almost zero, but I place a high value on its usefulness. I can move, transport large paintings, or haul a square yard of dirt, which seems worth insurance and licensing rates that are as low as they come. Still, the laundry list of my truck’s terminal dysfunctions is long, too many and too expensive to be worth fixing. It has no air bags. There's an exhaust leak in the cabin. I've been told that one of the tires has a slow air leak that just has to be watched, forever. Worst are the declining vitals: worn down engine, deteriorated gasket head, grimy valves, and splitting tubes.

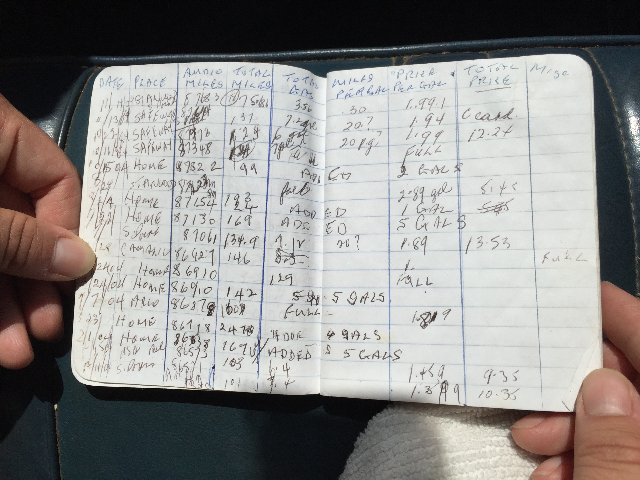

My favorite disrepair is the broken gas gauge, stuck at 3/8 full. The truck comes with a small logbook where my grandpa would record every gas fill next to the truck’s current mileage, along with the mpg, location of gas station, and how much gas cost that day. Now I continue the logbook, picking up where he left off. I enter in each column and check it against the past. With a full tank, I note the odometer and know that I have approximately 200 miles before I reach empty. Driving without the ability to constantly check the gas tank status requires some faith in the handmade system. As I drive, I track the miles and move the needle on the gas gauge in my mind. It’s funny how a grandparent can pass down a behavior by way of a seemingly inanimate object.

Before I inherited his truck, I would visit Grandpa at his house on Camano Island. Grandpa had made his living by building, selling, then moving from houses, and the Camano Island house was the one he’d kept. Sometimes I’d arrive and he'd be working on handmade concrete pavers for a section under the deck. He’d been doing projects like this one long before DIY became a cool thing, back when it was just what people did. He could only work on the pavers little by little, maybe two this week, four the next. I know it made him happiest to feel useful, to be moving ever forward, even if that progress had slowed with the pace of aging.

I’ve received many lessons in frugality from my grandpa, lessons that come in handy as an artist. My Grandpa rinses and reuses every zip lock bag, keeps scrap materials in his crawlspace, and saves leftovers in a deep freezer, sometimes for years. One time he took out a frozen jar clearly labeled “bean soup/2005” and handed it to me. I didn’t plan on ever eating it, but then times were tight, so I eventually ate the old soup.

It was during these visits that Grandpa would open up to me about things that were very personal. He’d share his loneliness, trouble with making friends, and moments of depression. The death of his wife and grudges from their old fights still bothered him. Talking helped him let these things go. He would share funny secrets, too, like the time my dad and uncles tricked Granny into caring for an illegal plant in her garden. Or he’d reveal a new crush he had. Some of these things might have seemed inappropriate to share with a granddaughter, but I was never easily shocked. In those moments we were also just two people, friends even, regardless of the sixty-five year age gap.

Nowadays, visiting Grandpa isn’t quite the same. He no longer lives in his house, but in an assisted living retirement home. This place has no garden to work in, no view of the sunset over the Sound, and no common sightings of bald eagles flying by. I believe living in his dimly lit one-room unit is getting to him. He routinely hides his belongings, worrying that someone with a master key is going through his things. He’ll then forget that he’s hidden it, and notice it’s missing, convinced that someone has stolen from him. The senior home has plenty of activities, but I imagine that to someone like my grandpa, these prescribed activities are just busy work. I imagine this because, like him, I too feel a need for some kind of ritualistic daily productivity, even if it is just putting a seed into some dirt. On the rare occasions I do make it out to the retirement home, I leave with a heavy heart—a guilty heart that I don’t see him more often. On days when the truck won’t start, I wonder if the universe is alerting me that my grandpa’s soul has moved on.

I know it doesn’t make sense for me to keep his truck, but I’m not ready to let it go. Grandpa didn't want to give it up either. During the truck transfer, he told me he had wanted to keep it around for escape just in case of a disaster. He leaned in and said, "That truck is worth some money, you know," looking me straight in the eye, just to make sure I knew it wasn't really a free truck. Part of me thinks it was also hard for him to finally let go of the last vehicle he owned.

People have emotional relationships with their cars. We catch ourselves coaching them up a long steep hill or begging them to make it just one hundred miles more. My grandfather represents a part of who I am, and so does his truck. I know that eventually the truck will give out, and I’ll be forced to sell it for parts, or possibly just for metal scraps. We’re only one year from turning thirty, my truck and I. My fingers are crossed that we’ll make it.

Devon Midori Hale is an artist from Seattle, Washington. She earned her BFA in Drawing and Painting at the University of Washington in 2009. Her painting examines themes such as family history, reverberations of intergenerational trauma, and mixed race identity. Last summer she attended the Jentel Foundation Artist Residency in Wyoming, and recently won the City Arts Art Walk Award.