This is the fourth essay by visual artist Veit Stratmann, who presented his project about the Italian city of L'Aquila at The Project Room in 2012. To read more about his research of the city that experienced an earthquake and has been forever changed, go here.

Read MoreWho Was Your First Hero, Sharon Arnold?

My first hero is totally a fictional character. I didn’t have a lot of good role models (who does?) so it’s probably not very surprising. I was born right in the middle of the 1970s, the same year the Runaways were born, and the year Lynda Carter first donned the strapless red, blue, and gold bootyshort costume that is iconically Wonder Woman. I will never forget her.

It’s ridiculous to watch it now. It’s super campy and the plot line is – I don’t even know what it is. She gets the bad guy and looks great doing it. But Lynda Carter is still the sexiest thing I’ve ever seen on television and her disco glam version of Wonder Woman will always be first in my heart. When I was four, I was inseparable from the bracers and crown that I would make out of paper and I would wear everywhere until they fell apart. When they did, I made more. My grandmother (who raised me) would help me carefully wrap the poster board in foil so it would be “metal” and I’d color it with a yellow marker to make it gold. If my grandmother insisted upon the removal of said adornment because of something as mundane as a bath, I’d yell indignantly. Greek goddesses don’t need to remove their armament to bathe – they’re just magically amazing and nice-smelling. They probably don’t even need baths. How silly to even suggest it.

Later, in 2nd grade at a school carnival, I was over the moon about a cardboard Wonder Woman at the photo booth. As I stepped up the ladder to put my head over her body the photographer exclaimed, “You look just like her!!” and I thought I would die. The resulting photo does not make any effort to hide the biggest, shit-eating grin I think I’ve ever worn.

As I grew up and got into comics, my love for her became deeper. It isn’t just that she’s drop-dead gorgeous, tall, athletic, independent, super strong, and invincible. It’s that she’s complex. Descended from Amazons and Greek mythology, she is expected to endure a world that is not yet ready for her. If she removes her bracers, she will be unfathomably powerful but she will also lose her mind. Once, she gave up her powers to stay here. She got them back. She’s smart as hell, using her wit and wisdom to solve problems, not using her beauty. She’s been through multiverses and spans a myriad of alternate Earths. She’s in love with Hades. She is presumed to love Superman. She is a warrior, but she is a woman.

The love affair blooms because she, like most Greek heroes, is who we aspire to be. The truth is that Wonder Woman is the ultimate human. She is not infallible. She’s emotionally layered. She has to make tough choices and they may not always be the right ones – there are consequences. We can do it all, but there is always a price. You can’t have everything. We can imagine ourselves in her place, doing the same thing, facing the same choices. It’s a fantasy – of course we could never be her. But, because she is human, we see ourselves in her, and we dream that some part of her exists in us, too.

Sharon is a Seattle-based artist, curator, and writer. She studied at Pratt Institute in New York and graduated Magna Cum Laude from Cornish College of the Arts, focusing on sculpture, art history, and philosophy. She is Founder of Bridge Productions/LxWxH and writes for her art blog Dimensions Variable and Art Nerd Seattle.

Some notes about the images: The Bather by William Bouguereau 1879 Photoshopped by FlashDaz for an online contest– I included it because it’s my favorite adaptation of Wonder Woman and it merges my art life with my superhero life; Wonder Woman’s New 52 costume. Panel from Justice League Vol. 2 #3 (Nov. 2011). Art by Jim Lee and Scott Williams; Wonder Woman in battle armor: 2003 DC Comics Wonder Woman: The Ultimate Guide to the Amazon Princess. –SA

Empathy Workshop: Share Your Stories

Musician, visual artist, and educator Paul Rucker has just begun his large body of work in reference to the US prison system, this history of slavery, and the current landscape of inequality and justice in current society. Titled Recapitulation, this thoughtful and provocative undertaking is being shared in-progress with The Project Room. Here, Paul introduces the subject, explains his interest in it, and asks for your stories.

Read MoreWho Was Your First Hero, Paul Marioni?

My first awareness of an adult public figure was of Mahatma Ghandi. At about seven years old, I would ask my parents “who is that old man in a diaper appearing in the newsreels.” I would say that my first “hero” was Bertrand Russell and his BAN THE BOMB movement when I was about eleven or twelve years old (1952 or 1953). I had been questioning my parents about the use of the atomic bomb in Japan as a child and our “duck and cover” drills in grade school and it just didn’t make sense to kill people (particularly me and my grade school chums).

Paul Marioni is one of the founding members of the American Studio Glass movement. He will be presenting stories from his life and work– along with a rare film screening– at The Project Room and Northwest Film Forum on October 2nd at 6pm. Read more about this program here. Photo of Marioni in a friend’s garden by Martin Janecky, 2013.

Who Was Your First Hero, Erin L. Shafkind?

First Heroes: Cowboys, Parents, Television

My heroes have always been cowboys.

And they still are, it seems.

Sadly, in search of, but one step in back of,

Themselves and their slow-movin’ dreams.

-Recorded by Willie Nelson, 1980, but first released by Waylon Jennings in 1976, and written by Sharon Vaughn.

That song plays in my mind when I think of heroes. My dad took me to my first concert, Willie Nelson, in 1982 when I was twelve. At thirteen, I witnessed my second concert, Laurie Anderson, with my mom. O’ Superman, Oh Mom and Dad … They divorced in 1976, and just knowing their musical tastes I understand why. But there’s true complexity in all relationships and, while I get that my parents could not stay married, deep down I wanted a ‘normal’ family. So where else would I find normal? On TV! On television, families seemed perfect and I wanted to be there.

On The Brady Bunch I could be a fourth (brunette) sister, and on The Facts of Life I would easily have been a boarding house girl with Mrs. Garrett, and have Tootie and Natalie as my best friends. I looked a little like Molly Ringwald, who starred in the first season, and growing up in LA, I once was accused of being her by a homeless man.

I loved television and would memorize all the intro songs to my favorite shows and sing them with friends on the swing sets after kindergarten. Swinging high on the swings and singing those tunes felt a tiny bit closer to connecting. Except for the time I accidently kicked a teacher in the head who was walking by: she came too close to the entertainment. Fame did not appeal to me, it was more that I related to how family appeared, and how easily conflict was resolved in the 22 minute sit-coms or the 48 minute comedy dramas.

I fantasized about being on Eight is Enough: they could have had nine, or squeeze me into Different Strokes: (‘What you talkin’ about, Erin!’)

I would’ve been a neighbor on The Jeffersons and, although I loved Good Times, I am not sure I could have been on that show as a white girl–but I still wanted to be.

Understanding the dynamics of race, class, and social position wasn’t in my knowledge base yet–I could tell time by TV, but age-wise we’re talking six to thirteen or so, and mostly I was really lonely. In some ways I am closer to Willie’s Cowboys than I might think:

“I learned of all the rules of the modern-day drifter,

Don’t you hold on to nothin’ too long.

Cowboys are special with their own brand of misery,

From being alone too long.”

I admit that I loved the Dukes of Hazard, but even as a young girl was bothered that Daisy Mae had to wear such short shorts; I found it embarrassing. I didn’t understand critical terms like the Male Gaze or objectification, but something sat funny. I just wanted to be part of their family and perhaps drive a fast car. They were maybe the closest I got to TV Cowboys though, since Bonanza seemed too old of a show, although it was in re-runs. I can’t forget Little House on the Prairie. I loved that show and could easily have been an adopted child like Albert. Living on the land, no electricity, going to a one-room schoolhouse, playing in the dirt, I could imagine it. Especially while eating Kraft macaroni and cheese during the cozy winters of Los Angeles in 1980.

My personal Emmy would probably have to go to The Love Boat.

It was Saturday night television at its best, a hodgepodge of characters coming together to help the passengers find love on the sea. (BTW, I have no desire to be on a cruise ship in real life, ever.) My ultimate fantasy? Captain Stubbing would discover me and ask me to come on the show as Vicki’s best friend. I’d drink Shirley Temples with Isaac, play shuffleboard with Julie, complain about queasiness with the Doc, goof off with Gopher and then sit at the Captain’s table with Vicki and her Dad at dinner.

I used to think it was sad that I watched so much TV, but I now believe that it helped shape me. Eventually I could see the chimera and understand the evolution of pop culture in my brain. Loneliness is not a plague as much as a state of creativity if one is willing to wallow for a bit, process and transcend. Once I thought that TV had calf-roped me. Now I think it was really just opening doors, giving me a horse to ride into the sunset.

Erin Shafkind lives in Seattle, WA where she teaches, makes art, enjoys writing and loves taking pomegranates apart one seed at a time. Her favorite colors are red, green, and blue, although she’s partial to blue considering her house, car, and kitty all share the same hue. She still watches TV, but not as much, she also loves to walk at Seward Park, read books and magazines that are printed on paper, and wonders often about the clouds and other weather related phenomenoms. She left Los Angeles in 1988 for Northern California and later came to Seattle in 1997. She will probably stick around, practicing a little of everything and laughing whenever possible.

All images reproduced from a 2010 performance titled “My Life in Pictures”, 12 Minutes Max, On the Boards, Seattle, WA.

An Introduction to L’Aquila, Empty City

An earthquake shook the city of L’Aquila on the night of April 6, 2009. It killed 308 people and injured at least 2000 others.

Initially, in order to facilitate rescue worker access, any survivors who were able to use their own means to leave the city were asked to do so. About 35,000 people—nearly half the city’s population—left the area. The remaining residents, unable to fend for themselves, were housed in emergency tents set up between 3 to 15 miles outside the city limits.

Gradually these tents were replaced by apartment buildings and single-family homes built in a dispersed manner in the countryside surrounding the city. The construction of scattered housing for the L’Aquila residents was accompanied by an official ban on returning to homes within the L’Aquila city limits. Thus, the city was entirely emptied within hours after the earthquake.

Next, as a prelude to the eventual reconstruction of the city, it was decided that the city buildings should be systematically reinforced by elaborate “exoskeletons”—either scaffolding or steel beams running from one building to another. These exoskeletons were constructed with such a high degree of complexity and precision, and of such expensive materials, that their building cost alone absorbed the majority of funds set aside to restore the city. In some cases, it now would be less expensive to destroy certain buildings behind the scaffoldings than to deconstruct the supporting structure itself. The exoskeletons literally prevented L’Aquila residents from accessing their own homes resulting in the decision to evacuate the city and to maintain the population at a distance.

To further the organization of the eventual reconstruction of the city, a classification system was supposed to be drawn up in order to prioritize the reconstruction targets. The categories were to include the ranking of buildings in terms of their relevance in art history and of their importance in the visual unity of the city. Other categories were to be centered on structural or city-planning issues. The budget allocations and response time for each restoration were supposed to be based on these categories. However, the description of each category and the criteria for classification were never clearly defined. No money was ever allocated because no buildings were ever formally classified. Hardly any official restoration work has been carried out to date.

The combination of these two decisions—the evacuation of the city and ban on returning to the city—has left the city in a state of suspended animation. The city is physically present and even largely accessible and potentially functional. However, that which bestows sense and form to the city—life and the temporality that life generates—has disappeared.

To walk the streets of L’Aquila is to be constantly faced with the impossibility of synchronizing the temporality of a human being with the surrounding non-temporality. Instead of offering a complementary experience between the person and his or her town, the encounter between a human being and this city creates rupture, incoherence and absence of meaning. The city is no longer a “part of things”. The inhabitants have become “outhabitants”.

The geographical dispersion of L’Aquila residents and the ban on returning to pre-earthquake habitations “dissolved” not only the city’s society but also the city itself. The fact that the “city” is traditionally and structurally the basic unit of politics in Italy means that the dissolution of the city brings about the annihilation of political space and societal structures. The administrative structures of the city exist, but the space in which they take shape and make sense has disappeared.

If one accepts the premise that politics constitutes, among other things, the art of structuring and sequencing the collective temporality of a society, then the evaporation of L’Aquila’s political sphere and the suspension of time can be considered interdependent and mutually perpetuating. The city is frozen in (or out) of time—and everything is suspended in a motionless state.

As L’Aquila is in a state of suspended animation, much like the absence of molecular movement at 0° Kelvin, its immobility cannot be modified. Any change of status is dependent on the possibility of putting something in motion, but no structure capable of activity exists in L’Aquila. Likewise, the absolute immobility of L’Aquila cannot be objectified but only experienced, because “objectifying” implies the possibility of measurement. And just as it is impossible to measure 0° Kelvin (because that necessitates the use of an instrument that could be colder than absolute zero itself), the measure of L’Aquila’s immobility would necessitate a tool even less mobile than absolute immobility.

I observe the current situation in L’Aquila much like a rabbit, paralyzed by the sight of a serpent. I cannot look away, nor leave, although I know the danger is great—and this danger risks annihilating my posture as an artist.

I traveled to L’Aquila thinking as an artist. In other words, I assumed that my role as an artist would allow me to formulate questions, to initiate debate and to identify different problems in (hopefully) an appropriate and sufficiently intellectualized manner. However my status as an artist should not permit me to formulate any univocal answers nor to propose any solutions to the non-art-related problems encountered, because any such attempt would completely undermine the pertinence and ethical validity of my artistic action, making it null and void. It would make art disappear.

Once in L’Aquila, I realized (with both horror and fascination) that the current state of things there perfectly materializes certain notions that I ponder in my own work: breaches of meaning, porous borders, the blurring of statuses, the posture of the spectator, the individual as a responsible being, who assumes his choices and takes can take a stance.

The fact that L’Aquila has fallen out of time and out of context generates a void or black hole. This non-L’Aquila sucks all meaning out of the surrounding environment. The city is that gigantic rupture of coherence that I try to capture and construct in each of my pieces.

On one hand, I had to be interested by L’Aquila. To be disinterested in L’Aquila would deprive me of a vast treasure trove of data relative to my work. It would deprive me of a physical and mental journey to the core of a space that represents the basic foundations of my work. It would deprive me of the exploration of the materialization of the driving force that maintains my artistic action.

On the other hand, L’Aquila is in an unacceptable state. And this status calls for real change. It appeals to the formulation of an objective—something that I feel should be avoided in an artistic posture. The necessity of identifying a goal runs the risk of transforming anything that I might accomplish in L’Aquila into “social work”, canalizing my thinking towards a univocal “solution” to purely non-art related problems. Art runs the risk of disappearing by its mere presence. And this risk is all the greater in the absence of any societal or historical structures, for the introduction of an artwork in L’Aquila would confer a special status to the work, underlining it as the only thing with a clear meaning and structure. Art would run the risk of filling the void left by the absent social structures and of self-effacing in its own presence.

My hesitation was reinforced as I walked the streets of L’Aquila. I had the overwhelming sensation of being in temporal desynchronization as a living being, faced with the surrounding structures in their out-of-time zone. I felt my inability to integrate myself as a social being in this context, which was bereft of any coherence, of any structures or of any frames of reference. These impossibilities—and the ruptures of sense they created—intrigued me so much that I could not resist wanting to “do something”.

I could attempt to fill the void. However, this first approach would lead me to propose a solution. Or I could attempt to pressure the fault lines to their cracking point and explode the status quo. In this case, I might be able to propose an artistically appropriate gesture. However, this second approach would be extremely difficult to defend from an ethical point of view, given the specific case of L’Aquila and the additional suffering that might be caused to innocent people. In either case, the impact of any work placed in L’Aquila would be rendered null and void in the absence of a public.

The only possible approach in order to infiltrate the situation seemed to begin with the de-dramatization of the relevant vocabulary: I needed to transform the notions of “artwork” and “artistic action” into the simple word “gesture”. This term designates nothing other than the idea that an artist—which I am—makes and produces forms. This term is sufficiently vague that it can be used in connection with L’Aquila without being taken for an attempt at a social or political solution, without it conveying the notion of being in contradiction with the current situation or constituting itself as a potential corrective agent.

I decided that I should carry out my gesture with intense discretion by documenting what I saw, writing in order to outline the stakes and to reinstate the results of my observation.

For now, I have two words with which I can work: gesture and artist. I need to create a tension and interaction between the two. I find myself in an insoluble situation, much like Chuck Jones’ iconic Wile E. Coyote, legs churning and suspended in mid-air above the gaping canyon with the elusive roadrunner just out of reach. Yet this impossible posture seems the only viable approach.

Images, from top: Scaffolding installed in 2009; post-it notes outside a local bar containing messages to the town written by former residents; a renegade knitting installation on public steps- its lack of foot traffic underscores the emptiness of the town; scaffolding holding up much of the oratory of a local aristocratic family- Veit was informed by the owner that it would be less expensive to demolish the building rather than remove the scaffolding; a typical city block in L’Aquila.

Veit Stratmann is a German-born artist who lives in France. His work is often created for public spaces, and responds to locations that are undergoing major change. Follow the making of Veit’s new body of work about L’Aquila throughout TPR’s Failure series, and join us for a visit from the artist in January, 2013.

What’s the First Thing You Ever Made, Amanda Manitach?

The first thing I remember making dates back to age four. My parents bought me a full size waterbed at that age. They built a wooden frame for it and I climbed inside and made pencil drawings of funny, flower-faced people all over the plywood, underneath where the mattress went. So every time I moved the mattress I’d encounter this bizarro city of people with petals instead of hair and ears.

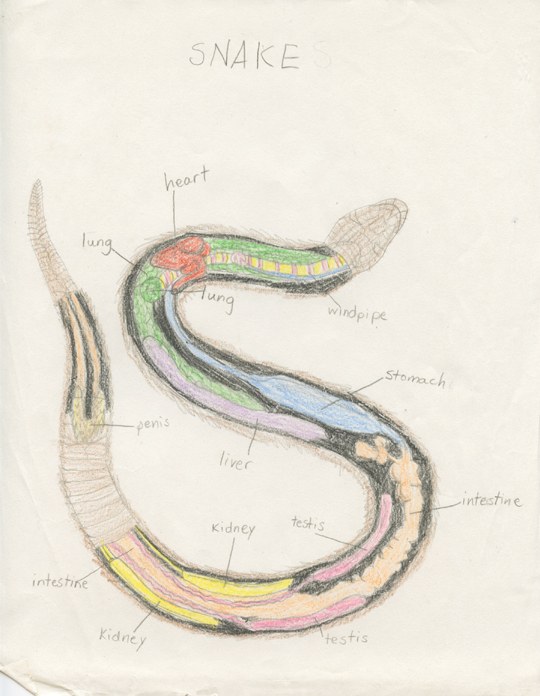

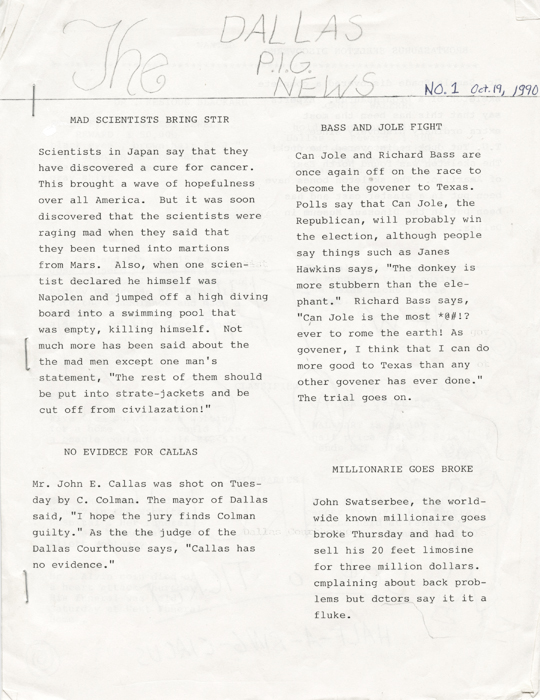

I always made a lot of publications as a kid—hand-drawn science magazines or mock newspapers pounded out, stream of consciousness style, on one of those newfangled Brother AX-28 typewriters.

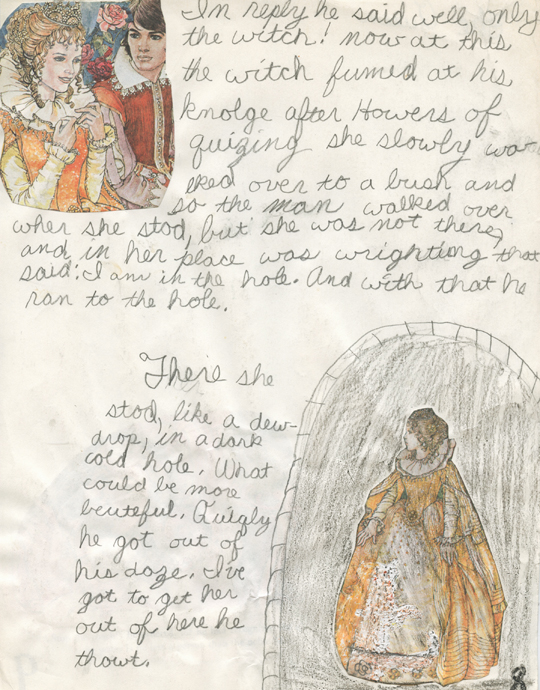

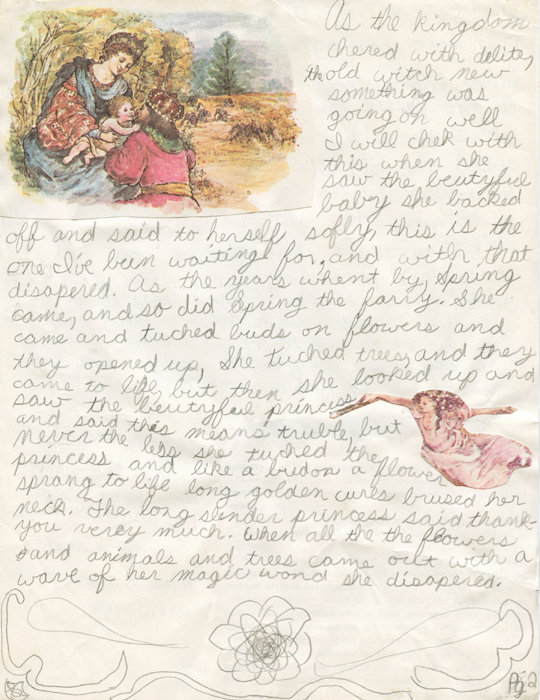

I have no idea when I wrote the fairy tale. The syntax is frighteningly similar to how I write today (although, thankfully, I’ve learned to spell a little better),

Finally, I was a nerd and a country girl and wanted very badly to be a naturalist when I grew up, running around with a butterfly net, collecting specimens from tide pools. In hindsight, I think this is a strictly bourgeois, Victorian occupation. I kept illustrated journals of all my fantastically exciting experiments, as all good Victorian schoolmarms do!

Amanda Manitach (www.amandamanitach.com) is a writer and artist based in Seattle, WA. It’s probably pretty obvious that she was homeschooled.

Notes from a Participant: “Dinner & A Movie”

On July 11 2012, TPR presented the second installment in the summer Art & Technology series as part of the Solutions topic. Titled “Dinner & A Movie,” the event asked two groups of artists and technologists to think, discuss, and debate their point of views around the topic “Debris & Value.” Tsunami debris, hoarding, unused ideas, classism, and all kinds of subjects were brought forth in front of an audience. The conversation was lively and much was revealed about how these creative makers approach issues.

Below are one some notes from the evening–a stream-of-consciousness “capture” of the conversation that unfolded:

Debris from French, 1708, related to bricolage and sabotage, sabo from sandal or footwear embroiled in protest, rubbish, to break—”are we defining debris or doing debris?” a filmmaker asks

hanging out on the periphery, fate not yet determined, remainders from catastrophe, toxic, man-made world, plastics, “love to eat awful,” group two’s facilitator begins

psychological debris

moving every year

are you minimalist or hoarder?

right angle or curved wall?

materiality of cyberspace

hardware built surrounding this space

wire forest with sunflowers and vines as people

“it’s okay to be a vine, must we always privilege sunflowers?” the screen retorts

merging inverses:

- class/food

- debris/value

- fetish/art

- artifact/virtual

- entropic/purposeful

- path of destruction/traces of creation

equations:

- what ended a life > what made up a life = forensics

- sculpture + time = debris

- space/debris = value

- “I saw you” ~ “I found this” = meaning

- performance junk < clean lines/pedestal + duster = residue

three closing thoughts:

– debris as hateful phrases left in the mind…

– Haida ceremony of destroying copper masks…

– plastic bags with dog shit found in the archaeological dig…

The Art & Technology Participants are:

Pete Bjordahl: Founder and CEO, Parallel Public Works

Ezra Cooper: Software Engineer, Google

Hsu-Ken Ooi: Founder, Decide.com

Charlie Matlack: CEO & Co-Founder at PotaVida; PhD Candidate at UW

Elisabeth Robson: Computer Scientist

Ethan Schoonover: Technology consultant, web designer

Korby Sears: Senior Producer, Discovery Bay Games; Principal Composer, Tejas Tunes

Sooyoung Shin: Software Engineer

Redwood Stephens: Mechanical Engineering Department Head, Synapse

Dave Zucker: Mechanical engineer, entrepreneur, designer, tinkerer

Byron Au Yong: Composer

SJ Chiro: Filmmaker

Lesley Hazleton: Writer

Jean Hicks: Milliner, visual artist

Bill Horist: Improvisational musician, Composer

Jeffry Mitchell: Ceramicist/Visual artist

Amy O’Neal: Dancer, Choreographer

John Osebold: Composer, performer

Stokley Towles: Performer

Claude Zervas: Sculptor/Visual artist

Matthew Baldwin: Writer

Brangien Davis: Arts & Culture Editor, Seattle Magazine

Jen Graves: Art Critic, The Stranger

Nancy Guppy: Producer and Host, Seattle Channel

Harmony Hasbrook: Designer and Writer, Parallel Public Works

C. Davida Ingram: Writer, artist, cultural worker

Charles Mudede: Social critic and filmmaker

Sasha Pasulka: Vice President of Product & Marketing, Salad Labs

Joey Veltkamp: Artist and Art Writer

Jenifer Ward: Associate Provost, Cornish College of the Arts; Editor, TPR’s Off Paper